When global oil prices shift dramatically, the stock market tells an interesting story. Some oil companies see their shares plummet while others surge upward on the exact same news. This split reaction isn’t random—it reflects a fundamental divide in how different types of petroleum companies make their money.

The oil industry operates much like a supply chain, with distinct stages from extraction to your local petrol pump. Understanding these stages explains why certain companies celebrate rising crude prices while others brace for financial pressure.

Upstream Companies: The Extractors

Upstream oil companies are the explorers and producers of the petroleum world. These firms focus entirely on finding and extracting crude oil and natural gas from beneath the earth’s surface or ocean floor. Their work begins with geological surveys to identify promising reserves, securing mineral rights, drilling exploratory wells, and eventually establishing full-scale production operations.

Think of upstream companies as farmers selling raw crops. When the market price for their product rises, they directly benefit because they’re selling the same volume of oil for more money. Their operational costs remain relatively stable—the expense of running drilling platforms and extraction equipment doesn’t change much with price fluctuations. This is why upstream companies like ONGC and Oil India see their stock prices climb when geopolitical tensions or supply concerns push crude oil prices higher.

The upstream sector is typically the most capital-intensive and technically challenging part of the oil business, requiring massive investments in exploration technology and production infrastructure. These companies remove basic impurities like water and sand from extracted crude before sending it along to the next stage of the petroleum journey.

Oil Marketing Companies: The Retailers

Oil marketing companies, often abbreviated as OMCs, operate in what the industry calls the downstream segment. These firms purchase crude oil, refine it into usable products like petrol, diesel, and kerosene, then distribute and sell these finished products to consumers through retail outlets and distribution networks.

Companies like Indian Oil Corporation, BPCL, and HPCL are examples of oil marketing firms that function as controlled intermediaries between crude producers and end users. In many markets, particularly in India, these companies face significant government oversight. They often cannot freely set their selling prices but must follow government-determined rates designed to protect consumers from volatile price swings.

This is where the squeeze happens. When crude oil prices spike, OMCs must pay more for their raw material. However, if government regulations prevent them from immediately passing these increased costs to consumers at the pump, their profit margins compress dramatically. They’re caught paying market rates for crude while selling refined products at controlled prices—essentially absorbing the difference as a loss.

The business model of oil marketing companies relies on marketing margins, which represent the difference between what they pay for crude and what they can charge for refined products. Unlike upstream companies that benefit from higher commodity prices, OMCs prefer stable or declining crude costs that allow them to maintain healthy margins while meeting regulated selling prices.

Why This Matters for Investors

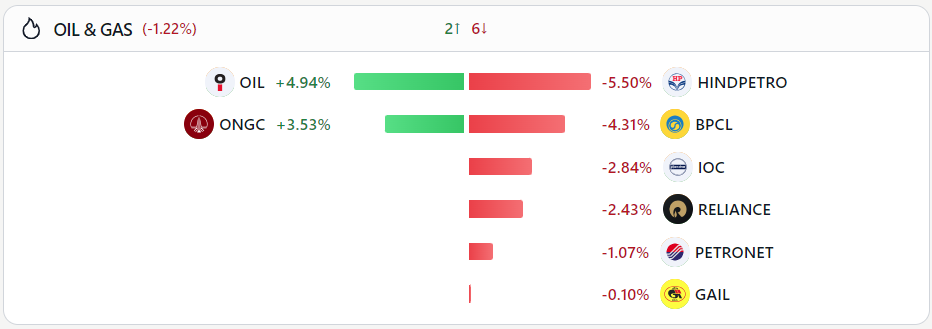

[The impact on upstream and downstream oil stocks in India when Brent crude futures exceeded $70 per barrel, marking its highest level in nearly six months.19Feb2026.]

For countries like India that import most of their crude oil requirements, this dynamic creates economic complexity. Rising oil prices benefit domestic upstream producers like ONGC and Oil India but squeeze the marketing companies like Indian Oil Corporation, BPCL, and HPCL that serve millions of consumers. Since most citizens interact with OMCs at petrol stations, government policy often prioritizes keeping fuel affordable, which shifts the burden of price increases onto these downstream companies.

This explains why during the same trading session, upstream and downstream oil stocks can move in completely opposite directions. They’re in the same industry but play fundamentally different roles with opposing relationships to crude oil prices. Understanding this distinction helps investors, policymakers, and consumers make sense of what might otherwise seem like contradictory market behavior.